As Fast as You Can Control

In Animal Flow we say, “Only go as fast as you can control.” But what exactly is ‘control’?

Control, or motor control as it’s officially known, refers to the way that your central nervous system interacts with the rest of your body, and the environment around you, in order to create well-coordinated and intentional movements.

Motor control is present in all movements. Everything we do–from something as simple as making a cup of coffee, right through to more involved tasks such as kicking a ball or driving a car–requires significant coordination to execute.

Control in motion

Motor control is no simple task; it’s a complex combination of various processes occurring in different systems in your body. Neural circuits, known as central pattern generators, work in conjunction with incoming sensory information to help create movement. In plain language, motor control is the term we use to explain how we generate, coordinate, and regulate movement in response to sensory input.

You can think of this sensory input as feedback that is collected and reported to the nervous system. This information helps you understand where you are in space and what action is required next in order to achieve an outcome. Sensory feedback comes from your ocular (vision), vestibular (balance), and proprioceptive (conscious perception of touch, pressure, temperature and positioning) systems.

The vestibular system

The three systems listed above function together. They each provide unique sensory information to the brain where it is integrated in order to determine what motion should be generated next.

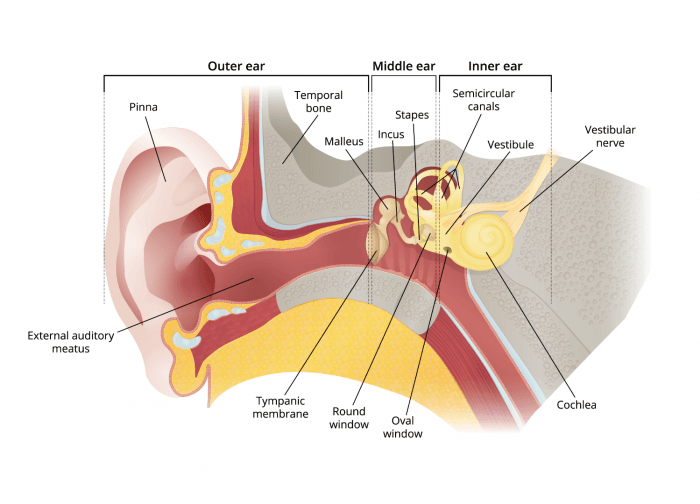

One system, in particular, plays a crucial role in our understanding of motion and spatial awareness: the vestibular system. It’s a complex organization of anatomical structures and pathways, primarily housed inside your inner ear.

Imagine you have a device in your ear that is a mix of a spirit level and an accelerometer. Whenever you’re in motion, your vestibular system constantly monitors the position of your head and body, as well as the speed at which you are moving, and reports this information to your nervous system.

Anatomy of the inner, middle and outer ear, including parts of the vestibular system.

You spin me ‘round

If you’ve ever spun around and around in a circle and then tried to run in a straight line, you’ll already have an awareness of your vestibular system.

At a fundamental level, you have three fluid-filled semicircular ear canals, each of which monitor a different direction of motion: (1) right and left, (2) up and down, and (3) side to side. When you move, the fluid (called endolymph) also begins to move, initially at a slower pace than you. This delay causes the fluid to stimulate sensory cells in your ear, providing information about how fast you’re going and in which direction.

Your ears are connected to your eyes

This sensory information from the vestibular system marries perfectly with your visual system. Try focusing at a point on your screen and, without looking away, rotate your head left and right. Note that your head AND your eyes are actually moving at the same time, but in opposite directions. As your head rotates right, your eyes will rotate to the left at the same speed in order to stay fixed on your focal point.

This eye movement helps to keep us balanced when we’re working at low speeds and within a moderate range of motion. Unfortunately we don’t have 360 degrees of vision, so once we begin doing full rotations, our eyes reach the furthest point they can before having to snap back to the start. This automatic eye movement is known as nystagmus.

In the same way that a gimbal or stabilizer creates a smooth picture when capturing video, your vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR) delivers a steady image to your eyes while your head is moving. This reflex is the result of the integration of incoming visual and vestibular information, and is incredibly valuable for balance and avoiding motion sickness.

Flowing through dizziness

Set Crab then perform a right leg Underswitch, left leg Underswitch, right leg Jumping Underswitch, right leg Full Scorpion, set Crab. Dizzy? That’s to be expected. Repetitive, one-directional rotations in your Animal Flow practice (which is one example of an ‘energy roll’) are bound to cause some dizziness.

Your vestibular system responds to changes in both speed and direction. Therefore, if you can maintain a constant speed during rotations, you’ll typically find that you’ll only experience the sensation of dizziness when you speed up or slow down. Yet when exploring various speeds and changing direction quickly in Flow practice, you aren’t typically ever attempting to stay on one trajectory or at a constant speed. So how can you use this knowledge to benefit your Animal Flow practice?

In the same way that you develop strength, endurance, or power by training it, if you want to get better at managing speed and dizziness, you need to habituate. Simply put, if you want to get better at fast rotations, do more fast rotations.

Check out this video below of Animal Flow creator, Mike Fitch, demonstrating an energy roll Flow.

Training for tolerance

- Take the short Flow from above or create your own.

- Complete the Flow at your fastest controllable speed, aiming to maintain a constant pace that induces a little bit of dizziness. It may take you a few attempts without stopping to reach that speed.

- As soon as you finish the Flow, hold your thumb around 4 inches (10 cm) from your face and stare at it until your dizziness subsides. Alternatively, stand up and lightly bounce on the spot until no longer dizzy.

- Once no longer dizzy and you feel ready, repeat the Flow at the same, or a slightly higher, speed.

- Again, focus on your thumb or lightly bounce at the end to reduce the post-rotation eye movement and settle the dizziness reflexes sooner.

- You can repeat the process as many times as you like on each side, but we recommend a minimum of 3 repeats.

- Stop if you start to feel nauseated as that’s a sign that you’ve hit your tolerance level for that session.

The great news is that, provided you don’t have a vestibular dysfunction condition, long-term training could result in excellent adaptations. A 2015 study from Nigmatullina et al reported positive changes to the brains of dancers that correlates with vertigo resistance. This means that training over time can help you to dull your sensitivity to spinning, allowing you to find better control in your Animal Flow practice at top speeds.

It’s also really important to note that dizziness, light-headedness, falling over or passing out could be indicative of something more serious. If you or a client are experiencing symptoms beyond a bit of light dizziness when performing energy rolls, we strongly recommend that you seek medical advice.

Ready to challenge yourself to the ultimate energy roll Flow? Try Flow #64 from Mike on Animal Flow On Demand and share it with us on Instagram. Use the hashtags #iinviteyoutomove and #animalflowondemand and share your practice with the AF community.